PUBLISHED : Saturday, 08 November, 2014, 11:11pm

UPDATED : Monday, 10 November, 2014, 2:02pm

A man straddles the Berlin Wall after the fall of communism in Germany in 1989. Photos: Corbis

Once the dust had settled, more than 40,000 segments of the wall were unceremoniously crushed to make materials for roads. The hated landmark, however, has left a profound and lasting impression, most notably on the popular imagination. Today the legacy of the wall and the cold war which ended when it came down lives on in novels, movies and music.

In literature, John Le Carré (who, under his real name David Cornwell, had worked for the British foreign intelligence service in Berlin) wrote his third book, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, published in 1963, in the divided city. It became his first bestseller and set Le Carré on his way to becoming the world's pre-eminent purveyor of spy fiction.

In 1965, a film version of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold was released starring Richard Burton as British spy Alec Leamas - but the wall and its aura of menace and foreboding upstaged the movie.

The wall and the cold war inspired Stanley Kubrick's Dr Strangelove

The wall and the cold war inspired Stanley Kubrick's Dr Strangelove"When I saw the Berlin Wall going up - I was there to flesh out our station in Berlin - when I conceived The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, which I wrote in five weeks, I was determined that he would be killed at the wall," Le Carre later said of his morally ambiguous anti-hero Leamas.

Alfred Hitchcock also drew from the wall in Torn Curtain (1966) starring Paul Newman. In 1987, German filmmaker Wim Wenders' fantastical Der Himmel Über Berlin (literally The Sky Over Berlin, or Heaven Above Berlin, but released internationally under the title Wings of Desire) follows two angels as they listen in on the troubled souls of the carved-up metropolis.

Music has also drawn significant creative inspiration from the wall over the decades, especially during the early and mid-1980s, when tensions between superpowers were high and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and other such political organisations enjoyed peak support around the world.

One of the catchiest wall-themed chart toppers was 99 Luftballoons (1983) by German band Nena, whose guitarist Carlo Karges had attended a Rolling Stones concert in Berlin in 1982. Balloons were released at the gig, and Karges ruminated on the terrible repercussions that might ensue if large clusters of balloons floated over the wall to be mistaken for something else on radar.

Later released as 99 Red Balloons in English to become a hit across the globe, the lyrics told of a boy and girl innocently releasing balloons and triggering Armageddon ("It's all over and I'm standing pretty," Karges trilled despairingly, "In this dust that was a city").

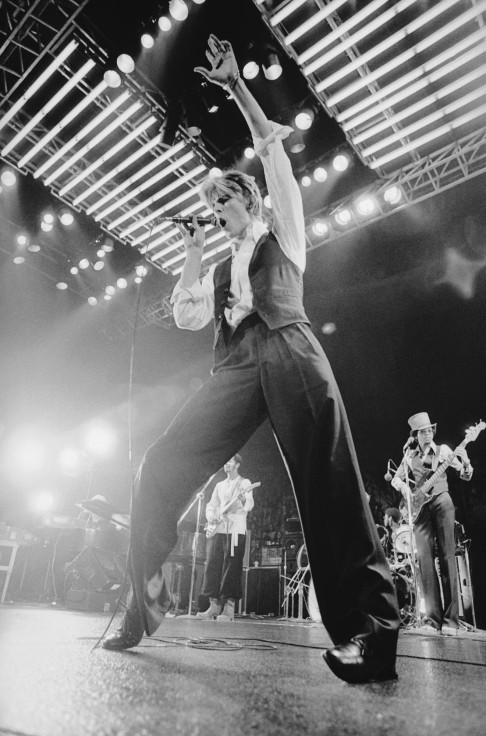

Pop star David Bowie

Pop star David BowieBerlin and the wall had influenced rockers before the 1980s. Punk pioneers the Sex Pistols' fourth single Holidays in the Sun was released in October 1977. According to lead singer John Lydon, an attempted break from media scrutiny on the British channel island of Jersey was unsuccessful so the band went to Berlin.

Ultimately, the fall of the Berlin wall did not mean an end of its influence on the mainstream imagination

Although Lydon described the city as "raining and depressing", the

group did enjoy what the lyrics called "a cheap holiday in other

people's misery" where "I didn't ask for sunshine and I got World War

Three/I'm looking over the wall and they're looking at me"."Being in London at the time made us feel like we were trapped in a prison camp environment. There was hatred and constant threat of violence. The best thing that we could do was to go set up in a prison camp somewhere else," Lydon said of the experience.

"Berlin and its decadence was a good idea. The song came from that. I loved Berlin. I loved the wall and the insanity of the place. The communists looked in on the circus atmosphere of West Berlin, which never went to sleep, and that would be their impression of the West."

For cultural chameleon David Bowie, Berlin in the second half of the 1970s was an escape from constantly living as his alter-ego creations (Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke in quick succession) and an out-of-control cocaine addiction. Based in the city for three years, sometimes sharing a flat with friend and collaborator Iggy Pop, Bowie made the so-called "Berlin Trilogy" albums: Low, Heroes and Lodger.

Pop's albums The Idiot and Lust for Life were also informed by his time in Germany.

John McTiernan's The Hunt for Red October

John McTiernan's The Hunt for Red October"David Bowie moved to the divided city not simply to find a new way of making music, but rather to reinvent - or to come back to - himself," says British non-fiction author Rory MacLean, 59, whose new book, Berlin: Imagine a City, was recently lauded by a reviewer at The Washington Post as "the most extraordinary work of history I've ever read".

"In the mid-1970s, [Bowie] realised he no longer needed to adopt characters to sing his songs. He found the courage to throw away the props, costumes and stage sets," MacLean says.

A moviemaker then, MacLean worked with Bowie in the studio where the musician had recorded Heroes just months earlier. "In that studio, from the control room, I saw the wall, as he had seen it," MacLean recalls. "From that control room, he had seen lovers kissing by the wall, and imagined the guards shooting above their heads, incorporating them into the lyrics. Berlin inspired Bowie, and stirred him to write about real, important matters."

Although the wall itself often played a lead role in many era-defining pop-cultural moments, the broader cold war - and the genuinely believed threat of nuclear holocaust and mutually assured destruction - were its joyless backdrop.

In popular music, Kate Bush's 1980 ethereal song Breathing concerns nuclear fallout. Prince's apocalyptic party anthem 1999 - released in 1982 - contains the lyrics, "The sky was all purple/There were people runnin' everywhere/Tryin 2 run from the destruction/U know I didn't even care". Then there was Ultravox's Dancing With Tears in My Eyes ("The man on the wireless cries again, 'It's over, it's over'") and UB40's self-explanatory The Earth Dies Screaming.

Director Alfred Hitchcock

Director Alfred HitchcockIn cinemas, Stanley Kubrick's acclaimed, surreal and nightmarish satire Dr Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb was released in 1964 when paranoia was high in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and when the wall was relatively new.

In popular literature, Tom Clancy's technically rich tales, such as 1984's The Hunt for Red October (later made into a blockbuster film of the same name starring Sean Connery) absolutely depended on a cold war setting.

The cold war, in fact, is a subject matter that has resulted in the worlds of film and literature crossing over and collaborating perhaps more than any other. It's unlikely that Ian Fleming's James Bond yarns would have landed on bookshop shelves - and subsequently been made into big-budget, hugely profitable feature films - during any other period.

Similarly, bestselling works by Alistair MacLean ( Ice Station Zebra), Richard Condon ( The Manchurian Candidate) and Donald Hamilton (his series centred around a ruthless US counter-espionage agent, Matt Helm, sometimes referred to as the "American 007", and with Dean Martin starring in the movie role).

And ultimately, the fall of the wall did not mean an end of its influence on the mainstream imagination, though time has taken the edge off the long-gone structure's ability to stir fear of the end of the world.

For example, Wolfgang Becker's internationally acclaimed feature film Good Bye, Lenin!, released in 2003 but set in 1990, tells of a young German man's elaborate machinations to keep secret from his ardent socialist mother - who has just recovered from a long coma - that the wall has fallen and her beloved East is no more. The movie is an unlikely comedy.

Punk rockers The Sex Pistols

Punk rockers The Sex PistolsWall expert Richard Schade, professor emeritus of German studies at the University of Cincinnati, cites Good Bye, Lenin! as a personal silver-screen favourite and an "exemplary filmic manifestation of the legacy of the fall of the wall". Schade, 70, says that modern-day commemorations of the wall's demise are also telling in how opinions have evolved with the years.

In 2009, two kilometres of massive Styrofoam "dominos" - each representing a concrete slab of the original fortification - were set tumbling to symbolise its demise. This year, German artists created a massive Border of Lights installation, lining up 8,000 illuminated balloons along the wall's route.

"Both anniversaries remember the once-upon-a-time wall, even as the wall is profoundly transfigured in these exuberant memory-culture displays," says Schade.

"It is the ultimate irony of history that the Berlin Wall - at which people died escaping; that symbol of a totalitarian cold war culture - now brings so much pleasure in modern-day united Germany."

No comments:

Post a Comment